Your phone’s operating system is basically a tiny city government: it hands out building permits (app installs), enforces zoning laws (permissions),

keeps the power grid stable (battery), and occasionally announces, “We’re repaving the whole downtown area tonight” (updates).

You don’t have to love itbut you do benefit when it’s well-run.

This guide breaks down how modern mobile operating systems (mobile OSes) work, what makes them different from desktop OSes,

and why iOS and Android feel similar in your hand while behaving very differently under the hood.

Expect real-world examples, a few jokes, and zero “the future is synergy” nonsense.

What Is a Mobile Operating System Today?

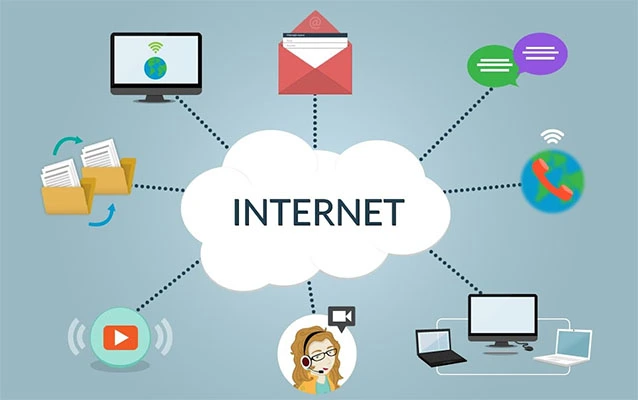

A modern mobile OS is the software layer that sits between your device’s hardware (camera, radios, sensors, GPU)

and the apps you actually care about (maps, chat, banking, games). Like desktop OSes, it manages memory, storage,

networking, and security. Unlike desktop OSes, it has to do that while:

- Living on a battery (the most dramatic power budget in computing).

- Being always connected (Wi-Fi, cellular, Bluetooth, NFC… the whole alphabet soup).

- Handling sensors constantly (GPS, accelerometer, gyro, camera, mic, biometrics).

- Staying secure in public (your phone is a wallet, a key, and a diary in one).

- Prioritizing touch-first UX (tiny screen, big expectations).

Modern mobile OS design is less about “running programs” and more about “running programs safely, politely, and without

turning your pocket into a space heater.”

The Big Players: iOS and Android

iOS: Integrated hardware + software (the walled garden with good landscaping)

Apple designs both the operating system and the devices it runs on. That tight control helps deliver consistent performance,

fast adoption of new OS versions, and a uniform set of hardware security features. It also means Apple decides

what’s allowed at the platform levelespecially around app distribution and system access.

Android: An ecosystem OS (the bustling city with many neighborhoods)

Android is built on an open-source foundation (AOSP) and ships across many manufacturers, price tiers, and device types.

That diversity is Android’s superpower (choice) and its permanent headache (variation). Google’s services and app store

experience are common on many devices, but not identical everywhere.

Both platforms aim for the same user outcomeapps that feel instant and safebut they get there with different

tradeoffs in openness, consistency, and control.

How a Mobile OS Is Built: The Layer Cake (No Calories, Plenty of Complexity)

1) Kernel and core system services

At the bottom is the kernel (the part that talks most directly to hardware and manages processes, memory, and drivers).

Mobile OS kernels are tuned heavily for power management and security boundaries. The kernel is also where “small bugs”

can become “big problems,” because it sits close to everything.

2) Hardware abstraction and device drivers

A phone isn’t just a computerit’s a computer welded to a camera, GPS, modem, secure element, and sensors.

The OS uses drivers and hardware abstraction layers so apps don’t need to know which camera module you have

or which vendor made your Wi-Fi chip. Without this, every app would need a “Works on Tuesdays” disclaimer.

3) Application frameworks

Frameworks are the official “how to do things” toolkits: render UI, play audio, show notifications, request permissions,

save files, call APIs, and run background tasks. Good frameworks provide power without handing developers a chainsaw

and saying, “Try not to cut the couch.”

4) The runtime and app model

The app model defines what an app is, how it’s packaged, installed, started, paused, and killed.

This is where mobile differs sharply from desktop: your app isn’t the main character.

The OS is. Apps come and go based on user attention, available memory, and battery health.

The App Life Cycle: Why Your Phone “Closes” Apps (And It’s Not Personal)

On a desktop, you can keep 38 tabs open and pretend you’ll read them. On a phone, the OS actively manages

what stays alive in memory. This isn’t cruelty; it’s survival.

Foreground, background, and “I swear I was doing something important”

Modern mobile OSes treat background work as a privilege. Android introduced strong limits on background execution

to reduce resource drain and improve user experienceparticularly around background services when the user

isn’t interacting with an app. That pushed developers toward scheduled work, foreground services for user-visible tasks,

and more battery-friendly patterns.

Result: better battery life for users, fewer “why is my phone dying at 2 p.m.?” moments, and more careful engineering for developers.

Security Model: The OS as a Bouncer, Not a Suggestion Box

Your phone is a high-value target. It carries authentication tokens, private messages, payment data,

photos, location history, and often the keys to your work accounts. So modern mobile operating systems

are built around defense in depth: multiple layers that assume something will eventually fail,

and try to contain the blast radius.

Sandboxing: apps live in separate apartments

Both iOS and Android isolate apps. In Android, each app is assigned a unique identity at the OS level and runs in its own process,

helping keep apps separated from each other and from sensitive system resources. In Apple’s platforms, runtime process security

leans on sandboxing plus entitlements (explicitly granted capabilities) and exploit mitigations like ASLR.

Permissions: asking nicely, but also proving you deserve it

The permission system is the OS’s way of saying: “You can’t just take the microphone because you had a vibe.”

Users see prompts like Camera, Photos, Contacts, Location, Bluetooth, Notificationsand increasingly, finer-grained options

like approximate location or limited photo access. Under the hood, those prompts map to policy checks enforced by the OS.

Verified boot and trusted startup

Security starts before the lock screen. Android’s Verified Boot is designed to ensure the code executed during boot comes from a trusted source

by building a chain of trust from hardware up through the verified partitions. Apple similarly emphasizes secure boot chains and hardware-rooted trust

mechanisms in its platform security model.

Hardware security: the “do not touch” vault

Modern phones include dedicated secure hardware for cryptographic keys and sensitive operations.

Apple’s Secure Enclave is one prominent example of a separate secure subsystem used to protect secrets

and support security features like device unlock and key management.

Mandatory access control and hardened policies

Android uses SELinux to enforce mandatory access control, restricting what processes can doeven if something gains high privileges.

Think of it as the OS putting certain actions behind locked doors with guards who do not negotiate.

Privacy: Not Just a Setting, but a System Design Problem

Privacy on mobile is tricky because phones are sensory machines. They can infer a lot from a little:

your commute, sleep schedule, friends, habits, and whether you went to that one store you “just walked past,” sure.

Modern mobile OSes respond with a mix of:

- Permission controls (who gets access to what, and when).

- Data minimization features (limited access, approximate location, scoped storage models).

- Platform policies (rules for what apps can collect and how they must disclose it).

- User-facing safety defaults (locks, device encryption, and account security prompts).

Government and standards bodies also publish practical guidance for managing mobile device risk in organizations,

because “every employee carries a networked computer” is a security architecture whether IT likes it or not.

Updates: The Most Important Feature Nobody Brags About

A modern OS isn’t “finished.” It’s maintained. Updates fix vulnerabilities, improve stability, and sometimes add features.

But update pipelines differ:

Android: monthly security bulletins + modular updates

Android publishes recurring security bulletins and security patch levels. Separately, Android also supports modular system components

(Project Mainline) where certain core modules can be updated via “Google Play system updates” on supported devices.

This helps deliver fixes more broadly than relying only on full device firmware updates.

iOS: centralized updates and rapid security responses

Apple provides OS updates directly to supported devices, plus an ongoing stream of security advisories for its software.

Centralized delivery simplifies “who gets what when,” though device eligibility still matters.

Practical rule for everyone: the “best” mobile OS is the one still receiving security updates.

Features are fun. Unpatched vulnerabilities are not.

App Distribution: Stores, Signing, and the “How Did This App Get Here?” Question

Code signing as a platform rule

Modern mobile OSes rely on code signing to help ensure apps haven’t been tampered with and come from known developers.

Stores layer additional review, policies, and enforcement on topvarying by platform and region.

Packaging formats and delivery

On Android, Google Play shifted new apps toward the Android App Bundle (AAB) format for publishing,

which enables optimized delivery (device-specific splits) and modern delivery mechanisms for large assets.

On Apple platforms, distribution is closely tied to signing identities and App Store policy compliance.

Enterprise Features: When Your Phone Is Also Your Office

Mobile OSes now include serious enterprise tooling because work moved into pockets years ago and never left.

Two common approaches:

Android Work Profiles (BYOD-friendly separation)

Android supports work profiles (managed profiles) that let IT control work apps and data in a separate space,

while keeping personal apps separate. The OS enforces that boundary so “company email” doesn’t casually leak into

your personal backup routines.

Apple MDM (policy and configuration at scale)

Apple supports Mobile Device Management (MDM) enrollment so administrators can configure devices, push policies,

install apps, enforce passcodes, and remotely wipe devices when neededespecially valuable for regulated industries

and large fleets.

Developer Experience: Building for Mobile Without Losing Your Mind

Developers don’t just “write an app.” They write an app that behaves well inside a strict OS environment:

- UI frameworks: iOS uses modern UI toolkits (like SwiftUI) alongside mature frameworks; Android uses Jetpack and Compose.

- Battery and background rules: background work must be scheduled or user-visible where required.

- Storage and privacy constraints: apps need to justify access, and often use scoped or mediated APIs.

- Distribution requirements: stores enforce packaging, policy, and (sometimes) review constraints.

The upside: users get apps that are harder to abuse, easier to uninstall cleanly, and less likely to ruin the whole device.

The downside: developers have to read documentation. (A moment of silence.)

Quick Comparison: iOS vs Android in Plain English

| Topic | iOS | Android |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware/software integration | Tight integration across Apple devices | Broad device ecosystem across many manufacturers |

| Updates | Centralized distribution to supported devices | Security bulletins + manufacturer updates; some modular updates via Play system updates |

| App sandboxing | Strong sandbox + entitlements model | Linux-based isolation + per-app identity and process separation |

| Enterprise management | MDM enrollment and configuration profiles | Work profiles and Android Enterprise management modes |

| App publishing | App Store policies and review requirements | Multiple stores; Google Play has specific publishing formats (AAB) and policy rules |

What’s Next for Mobile Operating Systems?

The big trends aren’t secret; they’re just quietly reshaping everything:

- More on-device intelligence: doing more processing locally for speed, offline resilience, and privacy.

- Stronger isolation: tighter sandboxing, hardened runtimes, and better exploit mitigation.

- More modular updates: separating critical components so fixes can ship faster.

- Identity and passkeys: fewer passwords, more device-backed authentication.

- Cross-device experiences: phones as hubs for watches, earbuds, cars, TVs, and mixed reality devices.

The “modern mobile OS” is no longer just for phones. It’s the operating fabric of your personal computing universe.

Which is inspiring… and also mildly terrifying if you never update.

Conclusion: The OS You Don’t See (But Feel)

Modern mobile operating systems are built to do three hard things at once: deliver a smooth user experience,

protect a mountain of sensitive data, and keep battery drain from turning into a daily crisis.

iOS and Android take different routesone emphasizing tightly integrated control, the other emphasizing ecosystem flexibility

but both rely on the same core ideas: sandboxing, permissions, secure boot, ongoing patching, and strict app lifecycle management.

If you remember only one thing, make it this: your mobile OS is your device’s immune system.

You can’t see it working most days, but you absolutely notice when it’s compromisedor outdated.

Experience Notes (About ): What It Feels Like in Real Life

The first time you truly appreciate a mobile OS is usually the first time it saves you from yourself. For me, it’s the moment you install a new app,

tap “Allow,” and then realize you just gave a flashlight permission to access your contacts, location, photos, microphone, andpresumablyyour childhood nickname.

Modern mobile operating systems have gotten much better at making that kind of overreach obvious. The prompts are clearer, the controls are more granular,

and the “only while using the app” options feel like the OS gently taking your hand off the stove.

On the work side, the experience is even more practical. If you’ve ever carried one phone for personal life and another for work, you know the special pain:

two chargers, two sets of notifications, and a constant fear that you’ll text your boss the meme meant for your group chat. Features like Android work profiles

(or managed configurations on iOS via MDM) change the day-to-day feel. Suddenly the device can be “one phone” without becoming “one big compliance nightmare.”

You can keep work apps in a dedicated space, let IT enforce security rules where it matters, and still maintain personal privacy. It’s not glamorous,

but it’s the kind of design that prevents a lot of late-night support tickets.

Developers feel the OS most intensely. Background limits, notification policies, and permission flows can be frustrating when you’re building something that

needs to run reliablylike a fitness tracker, a navigation app, or anything involving real-time updates. But after you ship an app and watch it run on thousands

(or millions) of devices, you start to understand why the OS is strict. If every app could run full-throttle in the background whenever it wanted, battery life

would become a nostalgic memory, like headphone jacks. So developers learn to work with schedulers, push notifications, foreground services, and platform APIs.

It’s like cooking with a timer you can’t disable: annoying until you realize it keeps your kitchen from burning down.

As a user, updates are the other “experience” that matters. You don’t feel security patches as a featureuntil you read about an exploit and realize your device

is either protected or politely volunteering as a case study. The OS experience is partly about trust: trust that apps are fenced in, trust that sensitive keys are

stored in hardened hardware, trust that the platform will keep tightening screws as attackers get smarter. The best mobile OS isn’t the one with the fanciest wallpaper.

It’s the one that quietly keeps your digital life boringin the healthiest possible way.