There are few sentences that feel weirder to type than “How to humanely kill a fish.” Yet if you keep fish, catch fish, work with fish, or simply want to do the right thing when a fish is suffering, you can end up heregoogling at 1 a.m. while your betta is having the worst day of its life.

The goal of humane fish killing (also called humane fish euthanasia) is simple: minimize fear, distress, and pain by causing a rapid loss of consciousness, followed by death. In practice, the “best” method depends on the context: aquarium pet vs. food fish vs. research/lab settings, the size and species of the fish, and what tools you have access to.

First: Euthanasia vs. Harvest (They Share Goals, Not Always Methods)

People land on this topic for two main reasons:

- Mercy euthanasia: A pet fish has a terminal illness, severe injury, or uncontrollable suffering.

- Humane harvest: You’ve caught or raised a fish for food and want to dispatch it quickly and respectfully.

Both should prioritize fast unconsciousness. The difference is that euthanasia methods used in veterinary and research settings often involve anesthetic agents and strict protocolswhile harvest methods emphasize immediate stunning/killing without introducing chemicals that could create food-safety issues.

What “Humane” Means for Fish (The Welfare Checklist)

Humane killing is less about what feels “gentle” to us and more about what reliably causes rapid insensibility. Good methods aim to:

- Reduce handling stress (less chasing, netting, and flopping).

- Induce unconsciousness quickly.

- Ensure the fish does not regain consciousness before death.

- Confirm death with objective checks (not vibes).

Fish welfare science and veterinary guidance increasingly emphasize that slaughter/euthanasia methods can meaningfully affect fish stress and sufferingespecially with slow methods like air asphyxia. When you can choose, choose the method that gets to unconsciousness fast.

Quick “Do This Before Anything Else” Safety + Ethics Checklist

1) Make sure you’re allowed to do it

If the fish is a protected species, someone else’s pet, or part of a regulated fishery, don’t improvise. Follow local rules and, when relevant, your state fish & wildlife guidance.

2) Decide whether you’re dealing with a pet fish or a food fish

This matters because many chemical anesthetics used for fish handling/euthanasia come with withdrawal periods and are not practical (or appropriate) for a fish that may enter the food chain.

3) If it’s a pet fish and you can reach a vet, that’s the gold standard

Aquatic veterinarians can use properly dosed anesthetics and confirm death reliablyespecially important when you’re emotionally fried and second-guessing everything.

The Most Humane Options for Pet/Aquarium Fish

Option A: Veterinary euthanasia (best when available)

If your fish is suffering and a vet is accessible, this is typically the most humane route. Vets can:

- Select an appropriate anesthetic agent for the species and situation.

- Ensure the fish reaches surgical anesthesia (unconsciousness) before death.

- Use secondary steps if needed to make death certain.

- Confirm death using reliable criteria rather than guesswork.

If you’re unsure whether euthanasia is warranted, a vet can also help assess quality of lifeespecially for chronic issues like advanced swim bladder disease, severe dropsy, untreatable tumors, or catastrophic injury.

Option B: Anesthetic overdose (the most common humane-at-home categorywhen done correctly)

In many institutional protocols, the humane core is: overdose an anesthetic to render the fish unconscious, then maintain exposure long enough to ensure death, and confirm with clear indicators (often including a secondary method in some species).

The most widely referenced fish anesthetic in U.S. guidance is tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222), used in veterinary, research, and fisheries contexts. Proper use typically involves accurate measurement and attention to water chemistry (for example, buffering is commonly required because the solution can be acidic). For many people at home, the practical barrier is that “close enough” is not good enoughprecision is part of what makes the method humane.

You may also see hobby discussions about clove oil/eugenol-based products. Some institutions allow eugenol-based products only when they are standardized and dosed accurately, because inconsistent concentrations can lead to unreliable outcomes. In other words: it’s not that “natural” automatically equals “humane”reliability and correct dosing are what matter.

Best practice mindset (without turning this into a chemistry lab in your kitchen): If you cannot confidently measure and follow a vetted protocol, don’t gamble. A method that is “supposed to” work but is performed inconsistently can prolong distressexactly what we’re trying to avoid.

Option C: Physical methods (humane in skilled hands, risky when improvised)

Physical methods can be humane because they can cause immediate insensibilityif performed correctly, with appropriate training and tools. In professional guidance, common physical categories include:

- Percussive stunning (concussive blow) to cause rapid unconsciousness, followed by a method that ensures death.

- Rapid destruction of brain function (often referenced in technical guidance as a follow-up step).

The downside is that an uncertain or poorly executed attempt can cause suffering. If you’re squeamish, rushed, or unsure, it’s better to choose a method that you can perform reliablyor involve a veterinarian.

The Most Humane Options for Food Fish (Anglers & Small-Scale Harvest)

If the fish is intended for food, the humane “north star” is: stun or kill immediately, then handle and chill the fish properly. Many welfare reviews note that common industry practices (like prolonged air exposure) can be inhumane, and stunning/killing methods that rapidly render fish insensible are better when feasible.

Option A: Immediate percussive stunning

Percussive stunning is widely discussed as a welfare-improving approach because it aims for instant insensibility. The key is correctness: wrong placement or insufficient force can prolong suffering. For that reason, many responsible anglers treat this like any other skilllearn it, practice the safe handling steps, and use appropriate tools.

After stunning, best practice is to proceed promptly to a method that ensures death and prevents recovery, then chill the fish. (This is also one reason humane dispatch is often linked with better flesh quality: less stress before death.)

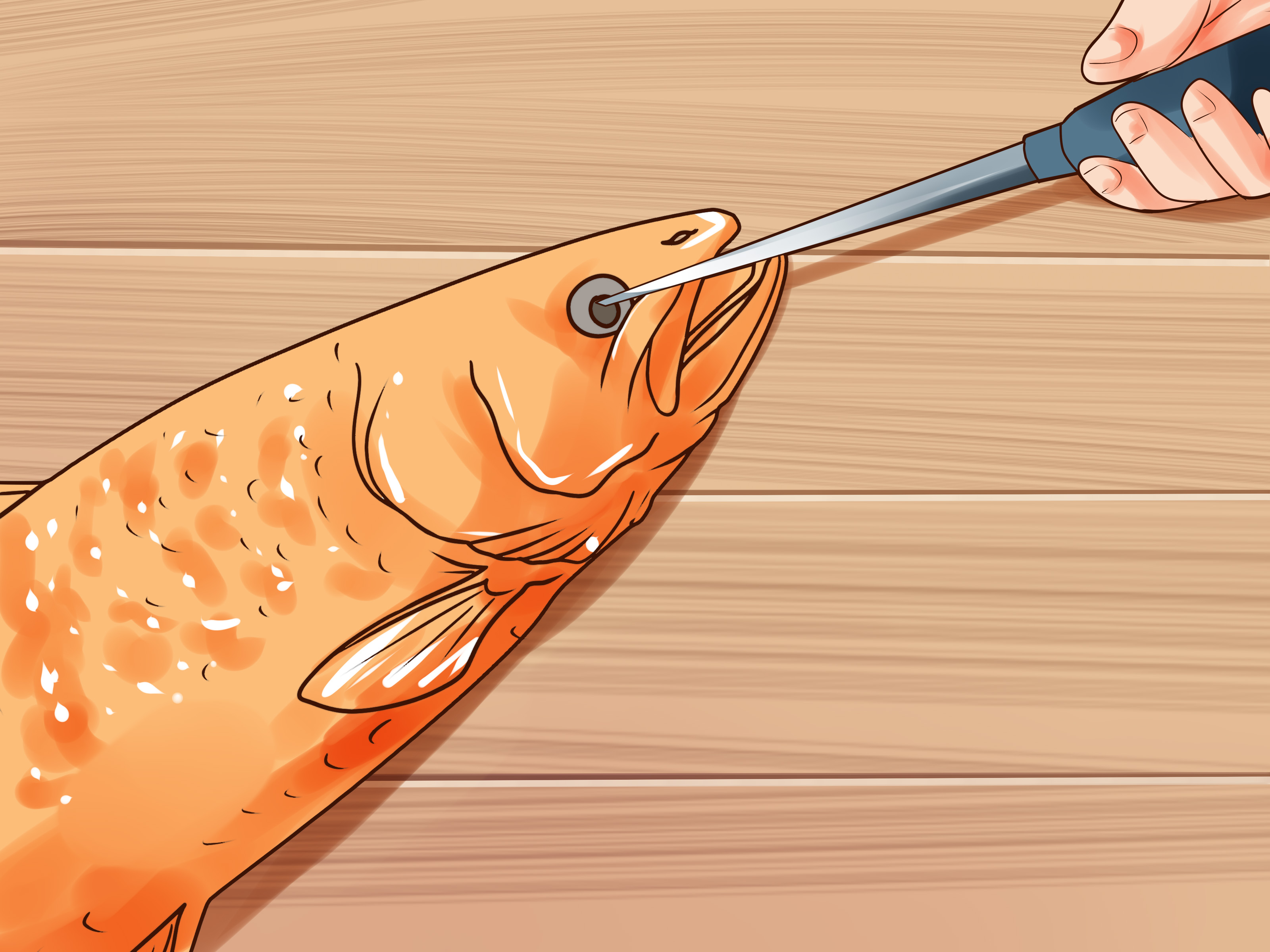

Option B: Ike jime-style dispatch (effective but skill-dependent)

“Ike jime” (and related techniques) are often described as humane and quality-preserving because they aim to eliminate consciousness quickly and reduce stress responses. However, multiple guides emphasize that it requires accuracy and training to be humane. If you’re learning, do so from reputable instruction and use appropriate toolsbecause a sloppy attempt defeats the point.

Option C: Electrical stunning (usually not a casual at-home method)

Electrical stunning is used in some professional contexts and can be humane when properly applied with the right equipment and settings. For most home anglers, though, it’s not the most practical routeespecially compared with a well-executed immediate dispatch method.

Methods to Avoid (Because “Common” Isn’t the Same as “Humane”)

Some methods are popular on the internet because they look simple. Unfortunately, “simple” can also mean “slow.” Veterinary guidance for pet fish commonly flags these as inappropriate or prohibited because they can prolong distress:

- Flushing (including exposure to chlorinated tap/toilet water).

- Freezing or slow chilling of a conscious fish.

- Air asphyxia (letting the fish suffocate out of water).

- Caustic chemicals or “DIY” poisons.

- Alcohol or boiling water (often suggested online; not humane).

If you remember one thing from this article, make it this: avoid slow, uncertain deaths. Humane killing is about speed and reliability.

How to Confirm Death (So You Don’t Accidentally Do the Worst Sequel)

Fish can be tricky because reflexes and some movement can persist even when the animal is insensibleand in some cases, cardiac activity can be an unreliable indicator. Many institutional policies and university IACUC resources focus on observable, repeatable criteria such as:

- No rhythmic gill/opercular movement for a specified period.

- No response to stimuli (reflex checks appropriate to the species/context).

- Maintain the euthanasia condition long enough (for example, staying in an anesthetic bath after opercular movement stops) to prevent recovery.

Practical takeaway: don’t rush. A humane process includes the unglamorous final step of waiting long enough and checking carefully.

Step-by-Step Decision Guide (Choose the Most Humane Method You Can Do Reliably)

If it’s an aquarium/pet fish:

- Call a veterinarian if at all possible (especially for larger or valuable fish like koi, or if you’re uncertain).

- If a vet isn’t possible, choose an approach that prioritizes rapid unconsciousness and reliability (typically anesthetic overdose via a vetted protocol, or a trained physical method).

- Avoid flushing, freezing, and suffocation.

- Confirm death using objective indicators and adequate observation time.

If it’s a food fish you caught or raised:

- Dispatch immediately using a humane method you are trained to perform (commonly immediate stunning/kill methods).

- Prevent recovery by promptly following through to ensure death.

- Chill properly (which is both a quality and welfare improvement when done after dispatch).

- Do not use anesthetic chemicals unless you fully understand legal use and withdrawal requirements.

Common Questions (Because Your Brain Will Ask Them Anyway)

“Is clove oil humane?”

Clove oil/eugenol is widely discussed in the hobby world. In formal settings, the big issues are standardization, accurate dosing, and reliability. Some institutional guidance allows eugenol-based products only when concentrations are known and protocols are followed carefully. If you’re not confident you can do that, a veterinarian (or a vetted alternative method you can perform reliably) is safer.

“Can I just put the fish on ice?”

“Ice” gets complicated. In some lab contexts, rapid chilling/hypothermic shock is discussed for specific small-bodied tropical species and life stages under controlled conditions and specific time requirements. That does not automatically translate to “ice is fine for any fish.” For general pet fish euthanasia, avoid slow chilling/freezing of conscious fish.

“How do vets usually do it?”

Veterinary guidance commonly references anesthetic overdose protocols and emphasizes avoiding methods like freezing and chlorine exposure (including toilet flushing). The vet advantage is correct dosing, appropriate drugs, and reliable confirmation of death.

Humane Disposal (A Quick, Un-glamorous but Important Note)

If you used any chemical agent, do not eat the fish, do not feed it to pets, and do not release it into the environment. For pet fish, disposal options vary by location, but generally avoid flushing and follow local sanitation guidance (some areas permit sealed trash disposal; others prefer burial where legal and safe).

Experience Notes: Real-World Situations People Run Into (and What They Learn)

The internet is full of “one weird trick” euthanasia advice. Real life is usually less tidy. Here are common scenarios fish keepers and anglers reportand the practical lessons that come out of them.

1) The “I tried treatment for weeks, and now I’m out of options” moment

A very typical aquarium story: a fish develops a condition like severe dropsy, chronic buoyancy problems, or a progressive infection that stops responding to medication. The keeper cycles through water changes, salt baths, antibiotics, and the emotional roller coaster of “maybe it’s improving?” The lesson many people share is that humane euthanasia is not “giving up”it’s refusing to prolong suffering when recovery is no longer realistic. The best outcomes happen when the keeper chooses a method that is reliable, not merely convenient, and confirms death carefully rather than rushing because the moment is hard.

2) The “I didn’t realize flushing was cruel until someone told me” realization

A lot of folks grew up hearing that flushing a fish is a normal way to handle death or illness. Then they learn that toilet water/chlorine exposure can cause distress and that “out of sight” is not “out of suffering.” People who make the switch often describe it as an uncomfortable but important upgrade in animal welfare literacylike learning that some “old school” pet care habits were simply wrong. The practical takeaway is that humane fish keeping includes planning ahead: knowing your vet options, understanding humane methods before you need them, and having the basic supplies or contacts so you’re not making high-stakes decisions in a panic.

3) The koi pond emergency (where size changes everything)

Koi and goldfish ponds can turn urgent quickly: a predation injury, a sudden ulcer, a crash after a cold snap, or a severe parasite outbreak. Keepers often report that what worked (or felt “doable”) for a tiny aquarium fish doesn’t scale to a 20-inch koi. This is where aquatic vets, mobile farm vets, or experienced pond professionals become invaluable. People who have been through this tend to emphasize two lessons: first, prevention and water quality reduce the chance of ever facing euthanasia; and second, if euthanasia becomes necessary, it’s worth getting professional help because the margin for error gets smaller as the animal gets larger and stronger.

4) The ethical angler shift: “If I’m keeping the fish, I should dispatch it fast”

Many anglers describe a turning point where they stop thinking of humane dispatch as “extra” and start viewing it as basic respect. They notice how long fish can struggle when left to suffocate, and they learn that immediate dispatch methods can reduce suffering and often improve meat quality by reducing stress. The “experience” takeaway is less about gear and more about mindset: if your plan is to eat the fish, plan to dispatch it quickly. If your plan is to release it, minimize handling, keep it in the water as much as possible, and release it promptly and carefully.

5) The “I want to do the right thing, but I can’t handle graphic methods” boundary

This is extremely commonand valid. Many people want humane euthanasia without having to perform a physically intense method themselves. What often helps is reframing: humane euthanasia is not a test of toughness; it’s a test of responsibility. If you can’t confidently perform a physical method correctly, choose a humane alternative you can do reliably (often professional veterinary care, or a carefully followed anesthetic protocol where appropriate). People who set this boundary often report feeling guilty at first, then relieved laterbecause the most humane choice is the one that actually prevents prolonged suffering.

Conclusion

Humane fish euthanasia is about compassion backed by competence. The most humane method is the one that reliably causes rapid unconsciousness and prevents recoverywhile avoiding slow, uncertain deaths like flushing, freezing, and suffocation. If you can access a veterinarian, that’s usually the best path for pet fish. If you’re harvesting for food, prioritize immediate dispatch methods that you are trained to perform correctly. Either way, take the final step seriously: confirm death with objective signs, and don’t rush just because the moment is uncomfortable.