Somewhere out there in the cosmos, invisible matter is quietly steering galaxies, bending light, and shaping the

evolution of the universe. We can’t see it, we can’t touch it, and we’ve never caught a single particle of it in the

labbut we’re almost certain it’s there. That mysterious substance is dark matter, and a growing

number of physicists are raising their voices to say: if the United States wants to stay at the front edge of

discovery, it needs to invest far more heavily in dark matter research.

In recent years, U.S. scientists have coordinated major planning effortslike the Snowmass 2021 community

study and the 2023 Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel (P5) reportto map out the most promising

directions for particle physics in the next decade. One theme keeps popping up: dark matter isn’t just important;

it’s central.

At the same time, budgets are tight, infrastructure is aging, and big science projects compete with everything from

fusion energy to climate research. That’s why physicists are making a clear, pragmatic case to the U.S. government:

dark matter funding isn’t a luxuryit’s a strategic investment in knowledge, technology, and long-term leadership.

What Is Dark Matter, and Why Does It Matter So Much?

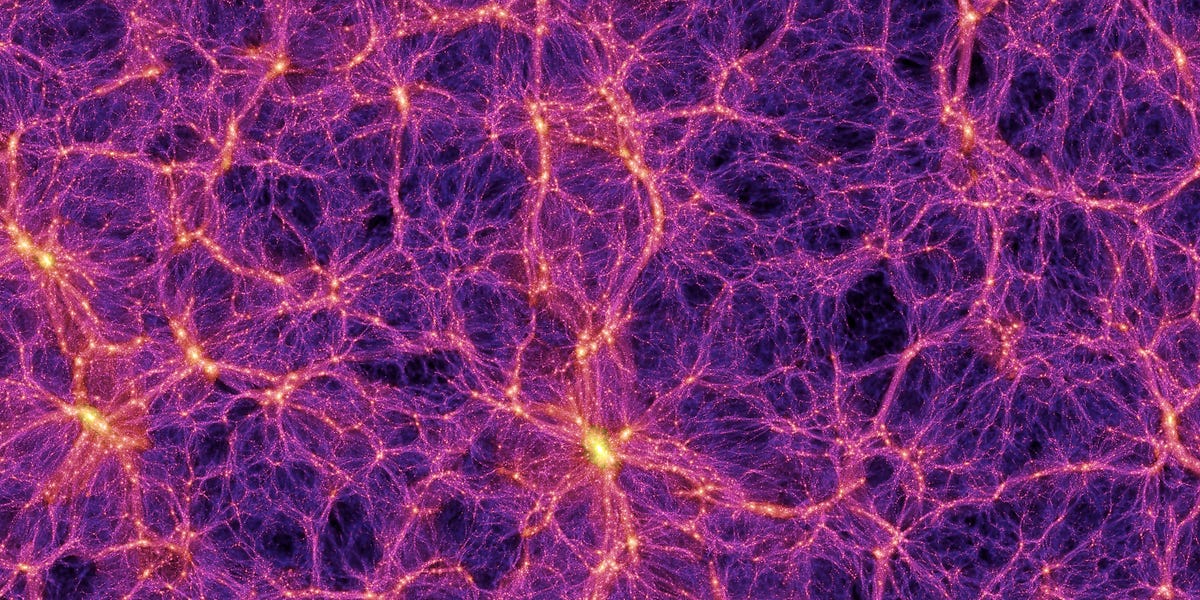

Dark matter is the name we’ve given to whatever accounts for roughly 85% of the matter in the universe.

It does not emit, absorb, or reflect light, which is why we call it “dark,” but it does exert gravity. We infer its

existence from several powerful lines of evidence:

- Galaxy rotation curves: Stars in the outer parts of galaxies move too fast to be held in place

by visible matter alone. - Gravitational lensing: Light from distant galaxies bends more than it should if only visible

matter were present. - Cosmic microwave background: Tiny fluctuations in the afterglow of the Big Bang match a universe

loaded with dark matter.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation describe dark matter as one of

the most pressing unsolved problems in modern physics. It’s not a side quest; it’s a core piece of the puzzle of how

the universe works at a fundamental level.

Cracking the mystery of dark matter would do more than satisfy our curiosity. It would reveal new particles, new

forces, or even new sectors of reality that don’t show up in the Standard Model of particle physics. In a field

where one discovery can rewrite textbooks and spin out entirely new technologies, that’s a big deal.

How the U.S. Funds Dark Matter Research Today

Despite all the mystery and excitement, dark matter research in the U.S. lives within very real budget lines and

bureaucratic rules. The work is primarily funded by:

- The DOE Office of High Energy Physics (HEP)

- The National Science Foundation (NSF)

- NASA and other agencies for related astrophysics and cosmology missions

These agencies support a mix of projects:

- Direct detection experiments buried deep underground, searching for rare collisions between dark

matter particles and ordinary atoms. - Indirect detection experiments using cosmic rays, gamma rays, and neutrinos to hunt for the

byproducts of dark matter interactions. - Collider experiments that try to create dark matter in high-energy collisions, then infer its

presence from missing energy.

Concrete examples include the Axion Dark Matter Experiment (ADMX) in Washington state, which uses a

giant magnet and a microwave cavity to listen for hypothetical axion particles, and large underground detectors like

LZ and XENONnT, which target another candidate called a WIMP (weakly interacting massive particle).

The U.S. has also committed to major cosmology and survey projects that double as dark matter observatories. The

Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a joint NSF–DOE project coming online in Chile, will take a 10-year

“movie” of the sky, mapping billions of galaxies and probing how dark matter clumps and evolves over cosmic time.

Over the years, DOE and NSF have issued dedicated calls for dark matter experiments and funded dozens of university

groups and national lab teams. For instance, a 2019 DOE announcement committed $75 million to high-energy physics

research, including dark matter and dark energy programs across U.S. universities.

So, is the U.S. already funding dark matter? Yes. Is it enough for the science community’s ambitions? That’s where

the debate heats up.

The Big Push: What Physicists Are Asking For

In 2021 and 2022, thousands of scientists took part in the Snowmass 2021 Community Planning Process,

a kind of massive brainstorming and consensus-building exercise for U.S. particle physics. One of the main outputs

was a set of dark matter reports emphasizing a “complementary” program: multiple kinds of experiments tackling

different dark matter possibilities instead of betting everything on one idea.

Building on that, the 2023 P5 reporta formal advisory roadmap requested by DOE and NSFlaid out a

10-year strategy. Among its recommendations:

- Support a portfolio of dark matter experiments, from large underground detectors to smaller, agile projects.

- Invest in infrastructure like expanded underground caverns at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in

South Dakota for neutrino and dark matter experiments. - Launch “agile experiments” under programs such as Dark Matter New Initiatives (DMNI) and the

new ASTAE (Advancing Science and Technology through Agile Experiments) framework.

In plain language, physicists are telling the government: “We need a mix of big, steady flagship projects and quicker,

cheaper experiments that can chase new ideas.” They argue that this diversified portfolio is the best way to survive

budget uncertainties and still keep moving toward discovery.

Competing Priorities and Tight Budgets

Of course, dark matter doesn’t exist in a vacuumat least not in the federal budget. The same agencies that fund

dark matter also fund:

- Neutrino experiments, including the massive DUNE project.

- Accelerator upgrades and future collider R&D.

- Cosmic microwave background (CMB) studies and dark energy surveys like DESI and CMB-S4.

The P5 report explicitly constructed its recommendations under two budget scenarios: a tight one and a somewhat more

generous one. Under the leaner scenario, some dark matter projects could be delayed or downsized. Under the more

hopeful scenario, the report calls for an “ultimate” xenon-based dark matter detector and a strong suite of smaller

experiments.

That’s where the urgency comes in. Dark matter research is not just competing with other big science projects; it’s

competing with every other national priority, from infrastructure to defense. Physicists are trying to make the case

before decisions harden into long-term realities.

Why Dark Matter Funding Is a Smart Bet

On the surface, spending millions of dollars to look for particles we’ve never seen might sound risky. But from a

long-term innovation perspective, it’s surprisingly rational. Large physics efforts have historically led to:

- Advances in detector technology that spill over into medical imaging, security, and industry.

- Breakthroughs in computing and data science, from distributed computing to machine learning

techniques now used by tech companies. - Training grounds for highly skilled scientists and engineers who later join the private sector.

The same cryogenic detectors that look for dark matter can inspire better radiation sensors. The same software that

analyzes billions of cosmic events can improve analytics in finance, climate, and AI. Historically, fundamental

physics has been a surprisingly good engine for real-world toolsjust ask the people who use the World Wide Web or

medical PET scanners, both born from particle physics labs.

What Better Funding Could Unlock

So what would increased U.S. government funding for dark matter research actually buy? Physicists tend to highlight

several key areas:

1. Next-Generation Detectors

New funding would allow the construction of larger and more sensitive underground detectors, capable of probing

weaker interactions or lighter dark matter particles than ever before. The P5 roadmap envisions an “ultimate” liquid

xenon experiment building on the successes of LZ and XENONnT.

Other experiments focus on ultra-light candidates like axions, using exquisitely tuned resonant cavities and quantum

sensors. These technologies are cutting-edge physics but also deeply connected to emerging quantum tech industries.

2. Cosmic Surveys and the Vera Rubin Observatory

Cosmological surveys are another major frontier. As the Vera C. Rubin Observatory begins its 10-year Legacy Survey

of Space and Time (LSST), increased funding can ensure the U.S. fully capitalizes on its datasupporting analysis

teams, computing infrastructure, and cross-links to laboratory experiments that test dark matter models.

Mapping how dark matter clumps on different scales could rule out entire classes of dark matter theories and steer

experimental design in smarter directions.

3. Agile, High-Risk, High-Reward Ideas

One of the most exciting trends is the push for smaller, faster, “agile” experiments. Programs like DMNI and ASTAE

are designed to let creative teams propose focused projects that can be built quickly, run for a few years, and then

pivot based on what they learn.

This is where truly weird ideas can get tested: dark matter made of ultralight fields, dark photons, or other exotic

candidates. Instead of locking all the money into a single mega-experiment, agile funding spreads the bets across a

wider terrainwithout blowing the overall budget.

What Happens If the U.S. Falls Behind?

Dark matter is a global race, not a solo mission. Europe, for example, is heavily invested in dark matter research

through CERN and underground laboratories in Italy, Spain, and elsewhere. China and other countries are ramping up

as well.

If U.S. funding stagnates, several things could happen:

- Brain drain: Talented young scientists may move abroad or leave fundamental research entirely.

- Lost leadership: The U.S. could miss out on hosting flagship experiments, which often become hubs

of innovation and training. - Reduced influence: In global collaborations, the countries paying the bills tend to shape the

scientific agenda.

We’ve already seen hints of this dynamic in other areas when budgets tighten, including proposed cuts affecting U.S.

participation in major international projects.

Physicists aren’t asking for blank checks. They’re asking for stable, predictable investments that keep the U.S.

meaningfully engaged and competitive in a field that may answer one of the biggest questions humans can ask: “What

is the universe made of?”

How Science Policy Responds to These Calls

When physicists urge the U.S. government to fund dark matter research, they rarely do it by shouting into the void.

The process tends to look like this:

- Community planning: Studies like Snowmass 2021 collect input from thousands of scientists and

distill it into consensus reports. - Advisory roadmaps: Panels like P5 use those reports to propose a prioritized research program

tailored to multiple budget scenarios. - Agency response: DOE and NSF respond to the recommendations by launching funding calls, new

initiatives, or construction projects. - Public and political discussion: Lawmakers weigh these scientific priorities alongside other

national needs when deciding overall budgets.

In other words, when headlines say “Physicists urge U.S. government to fund dark matter research,” they’re often

referring to this structured, multi-year effort to translate scientific opportunity into actionable policy.

Everyday Benefits: Why Non-Physicists Should Care

You might never visit an underground lab in South Dakota or analyze data from a Chilean telescope, but dark matter

research can still touch your life in subtle ways. Potential benefits include:

- New technologies: Better sensors, advanced materials, and ultra-low-noise electronics.

- Data and AI skills: Huge data sets from experiments push the limits of machine learning,

pattern recognition, and statistical modeling. - STEM workforce: Students trained in dark matter projects often move into tech, finance,

engineering, and other high-impact fields.

Even if we never detect a single dark matter particle (a possibility that keeps physicists awake at night), the

journey itself can change how we measure, compute, and innovate.

Inside the World of Dark Matter Research: Experiences From the Front Lines

To appreciate why physicists are so passionate about funding, it helps to zoom in from the big policy documents to

the day-to-day experience of the people and projects involved. Consider a few snapshots from the dark matter world.

A Night in the Underground Lab

Picture a graduate student at a deep underground facility, thousands of feet below the surface. The air feels

slightly different, the concrete tunnels are lined with cables and pipes, and the elevator ride down takes longer

than your commute to the grocery store. At the end of the tunnel sits a shiny metal tank filled with liquid xenon,

shielded by thick layers of water or rock to block cosmic rays.

This student’s task tonight is not glamorous: monitoring detector stability, checking calibration runs, and scanning

plots for signs of noise. Hours pass. The detector records billions of “nothing happened” events. That’s the norm

dark matter, if it interacts at all, is expected to interact incredibly rarely. The student jokes with colleagues

that their job is to stare at perfect emptiness and hope it’s imperfect.

Yet, despite the monotony, there’s an electric sense of possibility. If the experiment ever sees a clean, undeniable

signal that can’t be explained by known backgrounds, it might be the first direct detection of dark matter. The

people on shift that night would be part of history.

Life on the Data Tsunami

Meanwhile, miles away and far above ground, a postdoc working with Rubin Observatory data starts their day with a

very different kind of problem: too much information. The observatory will generate tens of terabytes of data every

night. Even early test runs produce more images and catalogs than a single person could inspect in a lifetime.

Their work blends astrophysics with data engineering: designing algorithms to spot subtle distortions in galaxy

shapes, or to track tiny shifts in position that hint at dark matter’s gravitational pull. They wrestle with cloud

computing, version control, machine learning frameworks, and the eternal question, “Is this a real feature or just a

bug in the pipeline?”

When budgets tighten, it’s often this kind of analysis work that feels the pinch. Hardware may already be built, but

without funding for people and computing, the scientific payoff shrinks. That’s one reason physicists argue that

dark matter funding can’t just be about building hardware; it has to include long-term support for analysis,

software, and training.

Writing the Case for the Next Experiment

In another corner of the community, senior scientists and early-career researchers team up to write proposals for

new dark matter projects. They juggle technical details (What sensitivity can we realistically reach?), logistics

(Where will we put it? Who will build which part?), and narrative (Why is this the right experiment at the right

time?).

These proposals don’t just drop numbers on a page. They tell a story about the scientific landscape: what previous

experiments have already ruled out, which dark matter models remain promising, and how their design fits into the

broader, complementary program outlined by Snowmass and P5.

When funding comes through, these proposals transform into jobs, hardware, software, and opportunities for students.

When they don’t, ideas may linger in limbo for yearsor vanish entirely as people move on to other fields.

Why the Community Keeps Pushing

Ask a dark matter physicist why they keep pushing for support, even after years without a definitive detection, and

you’re likely to hear a mix of humor and conviction:

- “We’re not lost; we’re exploring a map we’ve never drawn before.”

- “If dark matter were easy, someone would’ve found it already.”

- “Every time we rule out a possibility, we learn something real about the universe.”

For them, increased U.S. funding isn’t just about moneyit’s about keeping this spirit of exploration alive at a

meaningful scale. They know that dark matter may be stubborn, but history shows that persistent, well-funded,

collaborative science has a habit of turning impossible problems into tomorrow’s textbook chapters.

Conclusion: A Strategic Investment in the Unknown

Dark matter sits at the crossroads of curiosity and strategy. It’s one of the deepest scientific mysteries we know

of, and it’s also a test case for how a nation chooses to invest in long-term discovery. Physicists urging the U.S.

government to fund dark matter research more robustly aren’t just asking for money to chase a hunch; they’re

offering a carefully reasoned roadmap grounded in decades of progress, community consensus, and realistic budget

planning.

We don’t know whenor even ifa dark matter particle will finally appear in a detector or in the data from a sky

survey. But we do know this: if it happens, it will reshape our understanding of the universe and likely spin off

technologies and talents that reach far beyond physics. That’s why, in labs, tunnels, observatories, and committee

rooms across the country, physicists keep making their case: the unknown is worth funding.